2000irises: Born Inbetween — Lady Gaga and Born This Way

I’ve always admired Lady Gaga’s particular strain of brilliance. She’s barking mad and utterly fearless. Part pop-goddess, part freak show, Gaga does glamour and sex, but she also does nasty, ugly, and gross. She sings, she dances, she bleeds all over the stage. She wears raw meat. She travels by egg. For Lady Gaga, sex is lace and glitter, muck and filth. She wriggles about half-naked, and once she has your attention, she dives into slime and gore, as if to say “Call me sexy now. I dare you.” It’s a confusing sucker-punch, a bit taboo, but somehow annoying and delightful at the same time. No other mega-star can pull off the bait and switch like Gaga. She’s not Katy Perry and she’s not Ke$ha – she’s Cindy fucking Sherman with a microphone.

With that in mind, let’s think about the new “Born This Way” video. If you haven’t seen it, here’s the link to fix that problem right now. Don’t come back until you’ve watched all 7 minutes and 20 seconds.

This video pulses with cultural references, some you probably recognize, others maybe not. Aylin Zafar identifies many of them in her article for The Atlantic, “Deconstructing Lady Gaga’s ‘Born This Way’ Video.” Zafar deftly combs the video scene by scene, but her analysis is limited. She seems far more interested in cataloging the possible references than in considering why Lady Gaga would group these seemingly unrelated concepts together in a video.

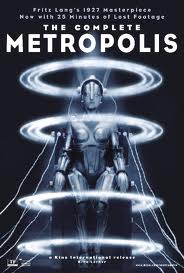

If you’ll allow me an English professor moment: “deconstruction” is only useful when we examine the details in order to gain greater insight into the whole. If we want to understand what Gaga is really trying to achieve with “Born This Way,” it’s not enough to simply point out the religious iconography or note the use of Bernard Hermann’s “Vertigo Theme.” Yes, there are visual references to Dali’s work (particularly his “In Voluptate Mors,”) the RKO logo, and Metropolis. The ending sequence nods to Michael Jackson and Madonna and Blade Runner. But why? What do all these references have to do with “Born This Way’s” ham-fisted message of self-love and universal acceptance?

One common theme explored by all of the films, artworks, artists and religious figures referenced in “Born This Way” is the danger of classifying the world into neatly defined polar opposites. Let me explain:

We open with the “Vertigo Theme.” Okay. Why? How is Queer Pride linked to Vertigo? One key source of tension in the film comes from the question of whether Judy or Madeline is the real woman to Scottie. He tries to turn each woman into a version of herself more like the other, but could there be a third option where they both exist? A real woman not at all subject to Scottie’s fantasies?

We open with the “Vertigo Theme.” Okay. Why? How is Queer Pride linked to Vertigo? One key source of tension in the film comes from the question of whether Judy or Madeline is the real woman to Scottie. He tries to turn each woman into a version of herself more like the other, but could there be a third option where they both exist? A real woman not at all subject to Scottie’s fantasies?

Next we see Gaga as the “good” Mother Monster: an ethereal goddess tricked out with a transcendent, insightful third eye.

Here, she’s the feminine ideal: intuitive, unattainable, pristine. Yet this goddess is bound in chains – even her birthing stirrups are chains. While there’s nothing remotely realistic about the birth itself – it’s shiny, glittery, glossy – it still manages to be somehow more honest than the clean, ascetic depictions of childbirth we often get. Lady Gaga may mimic the exalted image of the Blessed Virgin, but this is no immaculate birth. It’s sloppy and gooey. (Nota bene: real childbirth involves goo. You have been warned.) Cauls cover the heads of her children: disembodied androgynous robots. This goddess is both divine and bound to earth. She’s otherworldly, yet physical, fertile yet inhuman.

Then our lovely Mother Monster transitions into her “evil” counterpart. The camera climbs over writhing red figures (arranged into the image of a skull á la Dali) to find Lady Gaga all sexed-up, birthing automatic weapons and Dia de los Muertos figures.

She is evil because she brings death. But as we see, birthing death isn’t any less complicated than birthing life. Those skeletons can still dance, after all.

The Dali work referenced here is just one of his many pieces that explored the boundary between life and death summarily rejected it. He depicted otherworldly places where logic melts into fantasy and decay bumps against eternal youth. Consider “In Voluptate Mors” – the image of a skull composed of the healthy bodies of nubile women. Which is the most relevant concept in this work: the skull of death, the vigor of life, or the image itself that incorporates both while embodying neither?

The Dali work referenced here is just one of his many pieces that explored the boundary between life and death summarily rejected it. He depicted otherworldly places where logic melts into fantasy and decay bumps against eternal youth. Consider “In Voluptate Mors” – the image of a skull composed of the healthy bodies of nubile women. Which is the most relevant concept in this work: the skull of death, the vigor of life, or the image itself that incorporates both while embodying neither?

“Born This Way” also repeatedly borrows imagery from Fritz Lang’s 1927 film Metropolis, which asks us to consider which is more dangerous to society: a sexualized robot-woman who inspires lust and violence, or a pure-hearted flesh-and-blood woman who inspires love and hope among the repressed? For Lang, the two blend wickedly together, and the resulting monster must be burned at the stake, releasing the pure before destroying the wicked.

“Born This Way” also repeatedly borrows imagery from Fritz Lang’s 1927 film Metropolis, which asks us to consider which is more dangerous to society: a sexualized robot-woman who inspires lust and violence, or a pure-hearted flesh-and-blood woman who inspires love and hope among the repressed? For Lang, the two blend wickedly together, and the resulting monster must be burned at the stake, releasing the pure before destroying the wicked.

Then at last we have Gaga herself, pumping away in a sexy bikini. She’s not a goddess here, she’s not a robot, she’s not divine, she’s not evil. She’s just Lady Gaga doing what she does best: singing and dancing.

Some have suggested that her mostly-naked get-up contradicts her message of self-love and empowerment. But Gaga’s not telling anyone “don’t be sexy.” She’s not suggesting we find a cozy sweater and take up knitting. “Born This Way” is all about sex for heaven’s sake. She’s saying go ahead and be yourself, be sexy, sexy is fantastic. For Lady Gaga (and hopefully for us all,) ANY brand of sexy is just fine, even if it means stripping to your Underoos and writhing about with dozens of other people. She’s wearing a teeny-bikini, yes, but significantly, nothing else. Gaga’s stripped relatively bare here – no shoes, no elaborate wigs or headpieces, minimal (for Lady Gaga) makeup. She even has her hair in a ponytail at one point. Contrast that with the elaborate costumes of “Paparazzi,” “Telephone” or “Bad Romance.” Hell, contrast it with “Born This Way’s” goddess and robot costumes (can you imagine how long it took to get into those outfits?)

Other references in “Born This Way” take up the same themes. Is “Billy Jean’s” Michael Jackson a god-like Magic Man or a vulnerable human being capable of fathering a child? Which is the “real” Madonna: the flushed pseudo-bride of “Like a Virgin” or the dominatrix of “Human Nature?” Is Harrison Ford’s Deckard character in Blade Runner a human or a Replicant? The answer to all these questions is “somewhere in the middle.”

“Born This Way” may not be very subtle, but its labyrinthine video is. While the song plainly urges self-acceptance and kindness, the video reminds us why that’s so essential. By referencing works of art which question the tyranny of dualism, Lady Gaga reinforces that even our most primal, seemingly universal experiences never fit into neatly organized, labeled boxes. When we try to force ourselves into those boxes, we do harm. Lady Gaga’s futuristic utopia is a place where good and evil, life and death, male and female don’t really exist – everything here lies in between.

You must be logged in to post a comment.